All of us at Bevel Gardner and Associates would like to wish you and your family a very Merry Christmas! We hope you enjoy your time spent with family and friends. Merry Christmas!

Blog

Bevel Gardner & Associates forensic consulting and education providing instruction across the country and around the world. Located in Oklahoma, we are the largest independent forensic consulting company in the US. Follow our blog.

BGA Presents Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Level I in Wichita

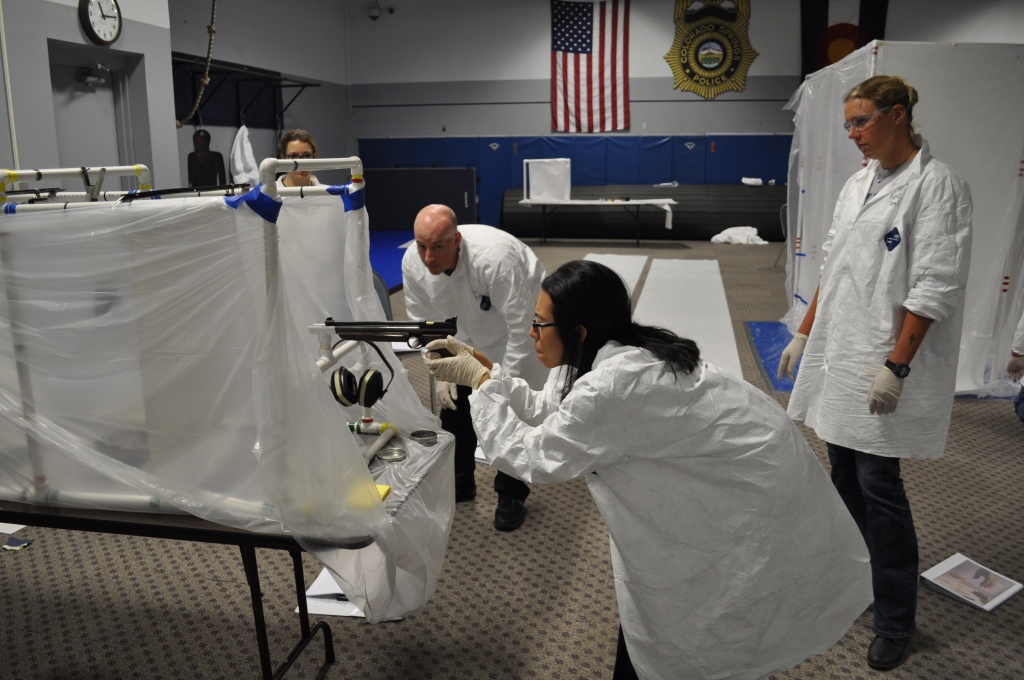

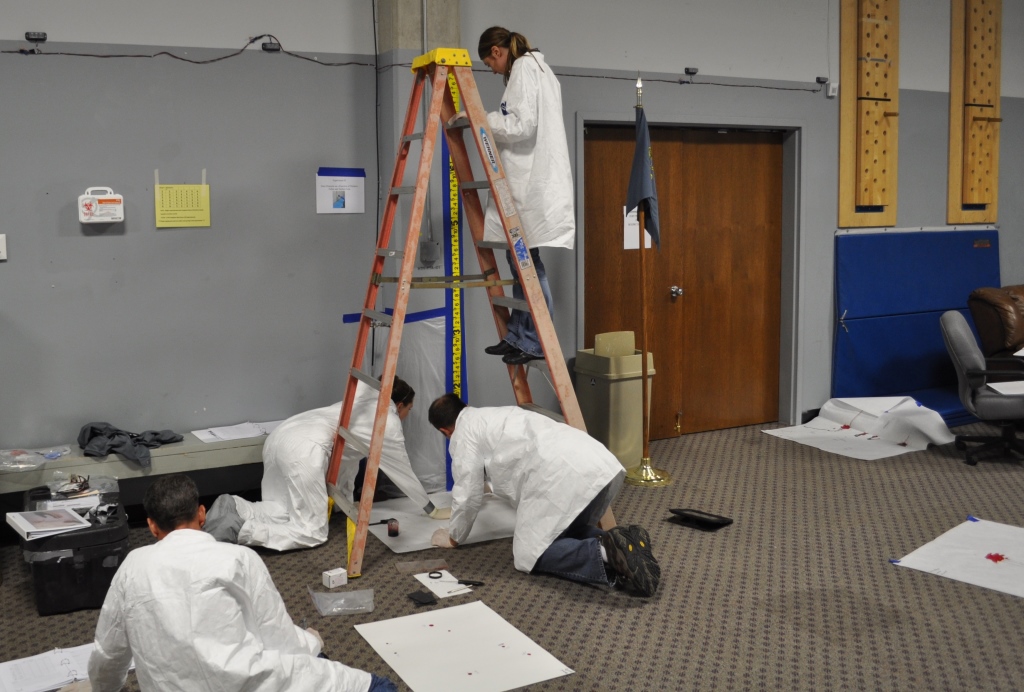

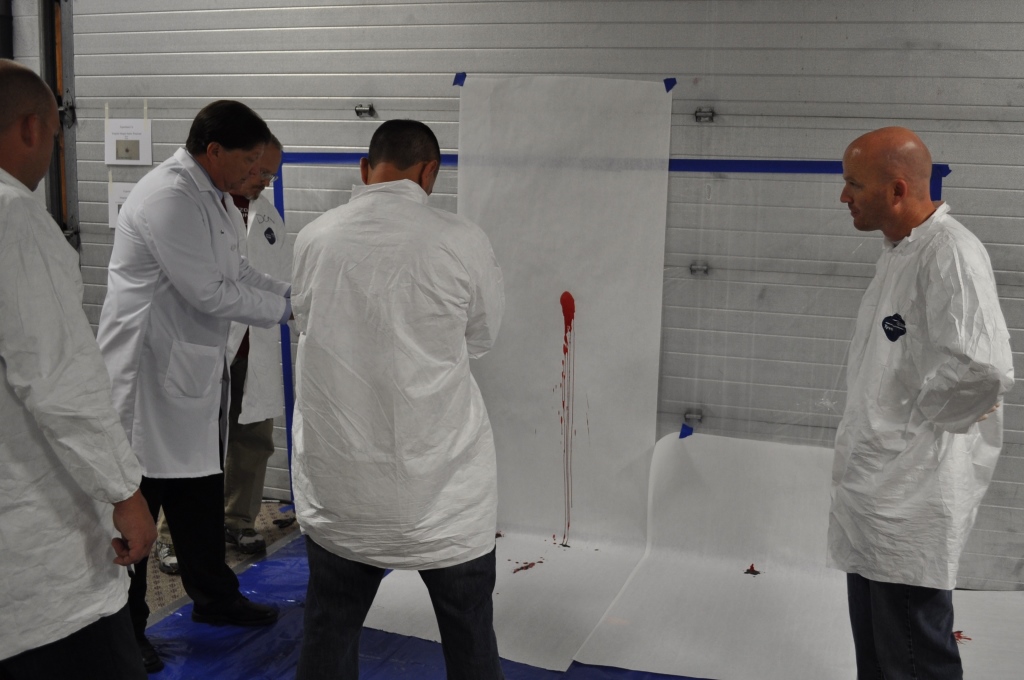

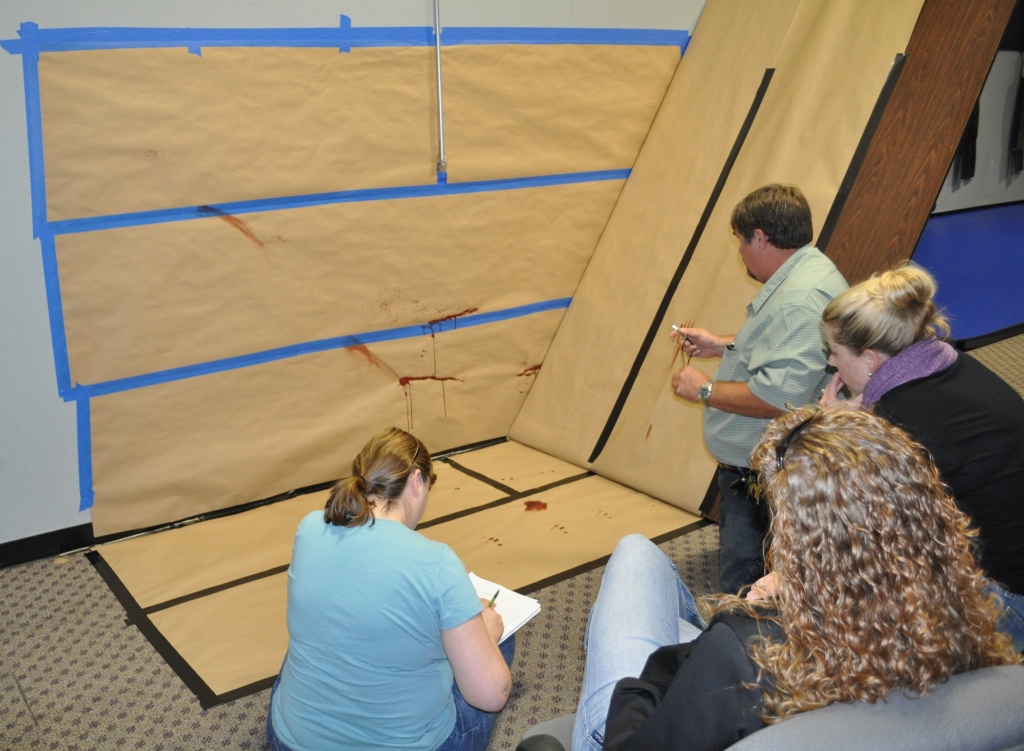

At the request of the Wichita Police Department, Bevel, Gardner and Associates conducted two back-to-back Level I Bloodstain Pattern Analysis courses in Wichita Kansas between November 30th and December 11th.

Ross and Iris instructed students from Wichita Police Department’s Crime Scene Unit and Detective Bureau as well as CSI’s as well as Detectives of the Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Office.

Ross Presents at the 7th Annual Asian Forencis Science Network Training Conference

Ross recently traveled to Kuala Lampur, Malaysia where he made two presentations to the 7th Annual Asian Forensic Science NetworkTraining Conference. He presented on the need for criteria based classification of bloodstain patterns and use of the BGA Decision Map as a classification tool. Ros also led a discussion of the importance of methodology in crime scene reconstruction.

Ross then presented a four hour class on Bloodstain Pattern Analysis at the RMP College for an audience of crime scene investigators at the request of the Commandant of the Royal Malaysian Police Training College.

Forensics Down Under

Bevel, Gardner & Associates forensics expert Ross Gardner recently returned from Australia, where the ACT (Australian Capital Territory) Branch of the Australian and New Zealand Forensic Society (ANZFS) hosted BGA Level I and Level II Crime Scene Reconstruction courses. Attendees included participants from the Australian Federal Police, Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria Police. The class was held in Canberra at the Canberra Institute of Technology. Ross also attended a meeting of the ANZFS on October 29 to discuss the need for criteria based analysis in bloodstain pattern analysis. Our special thanks go out to Eric Davies and Jodie Leigh Green of the Australian Federal Police who acted as Ross’ hosts, their Australian hospitality was second to none.

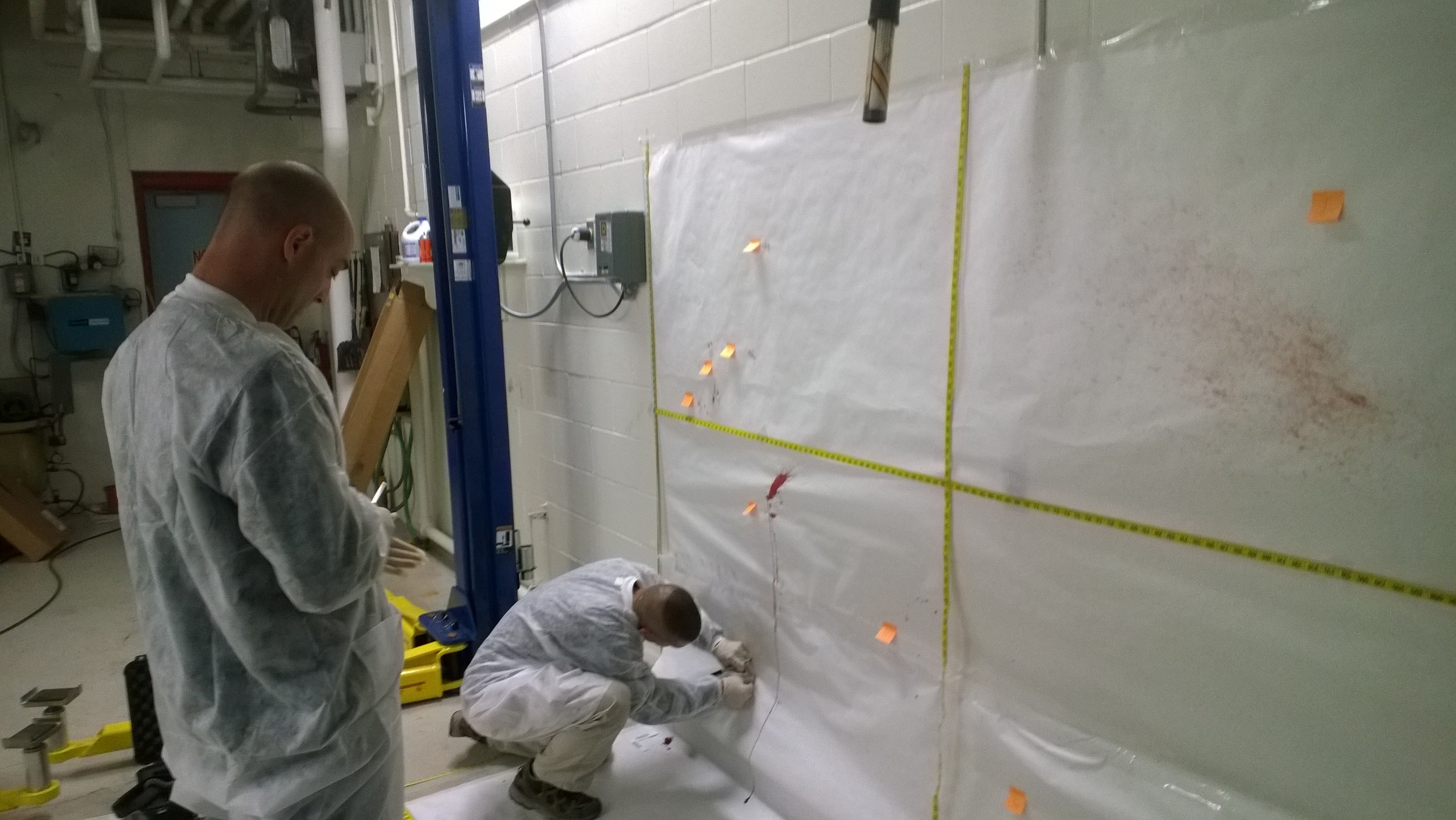

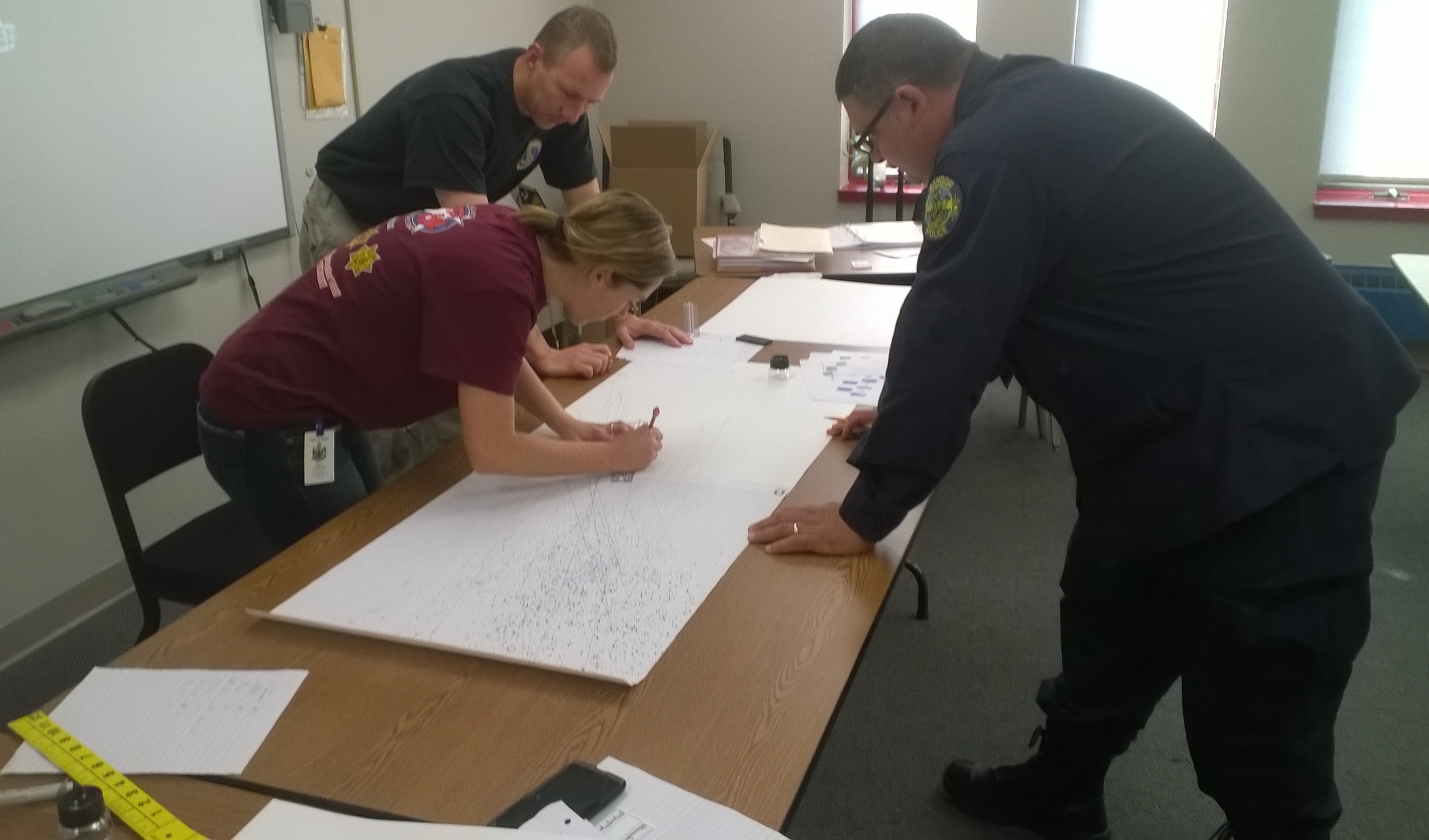

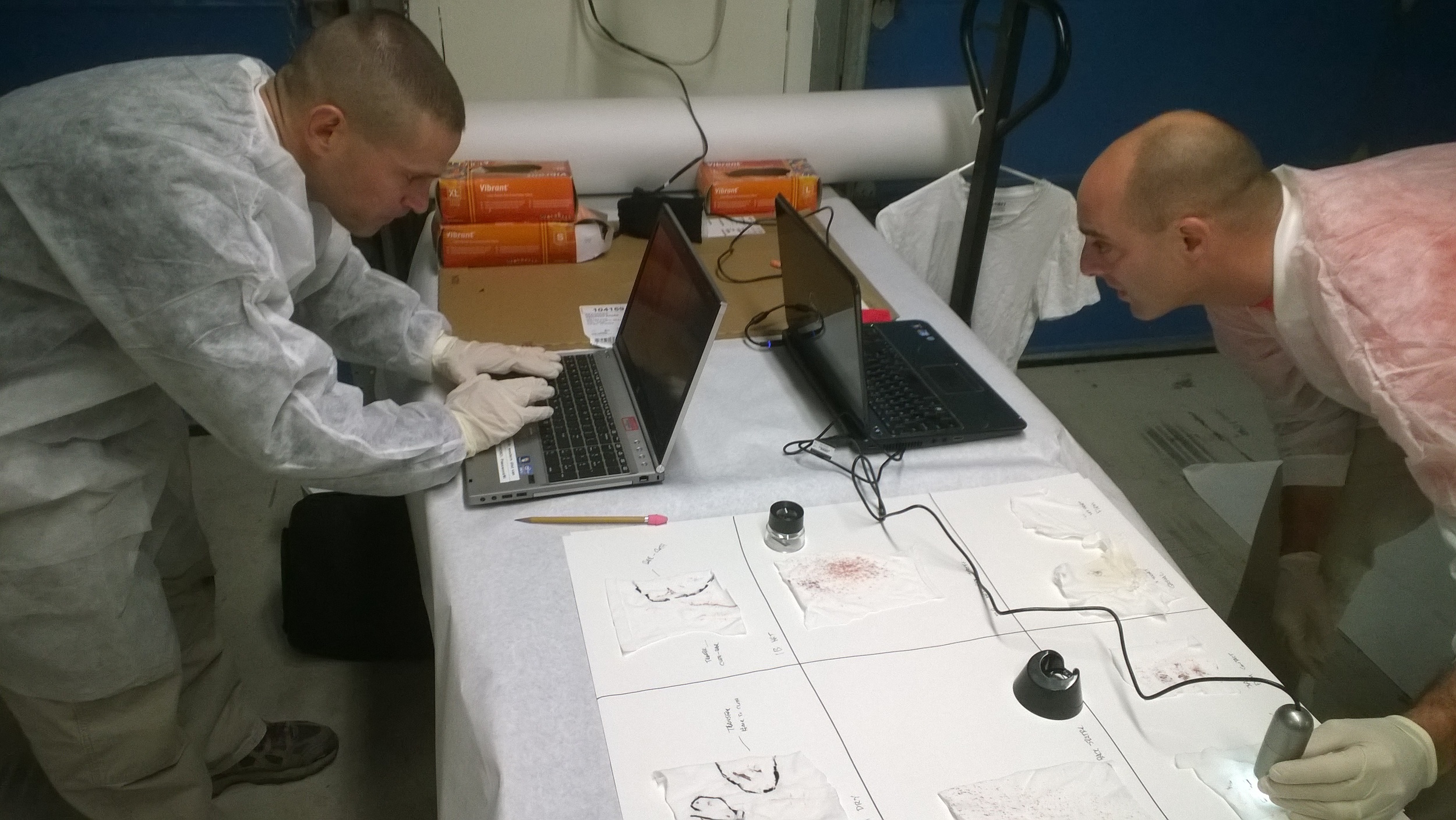

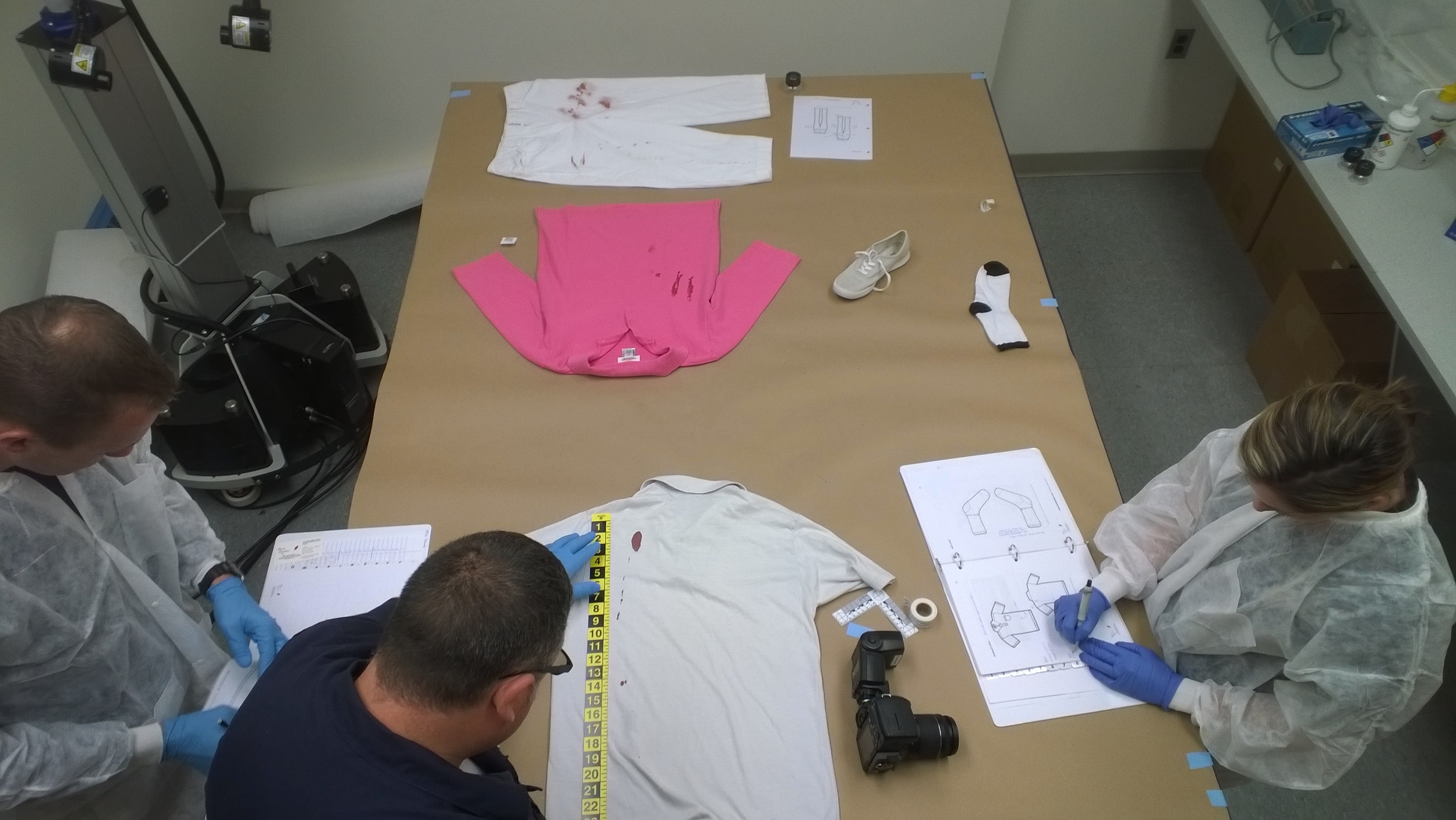

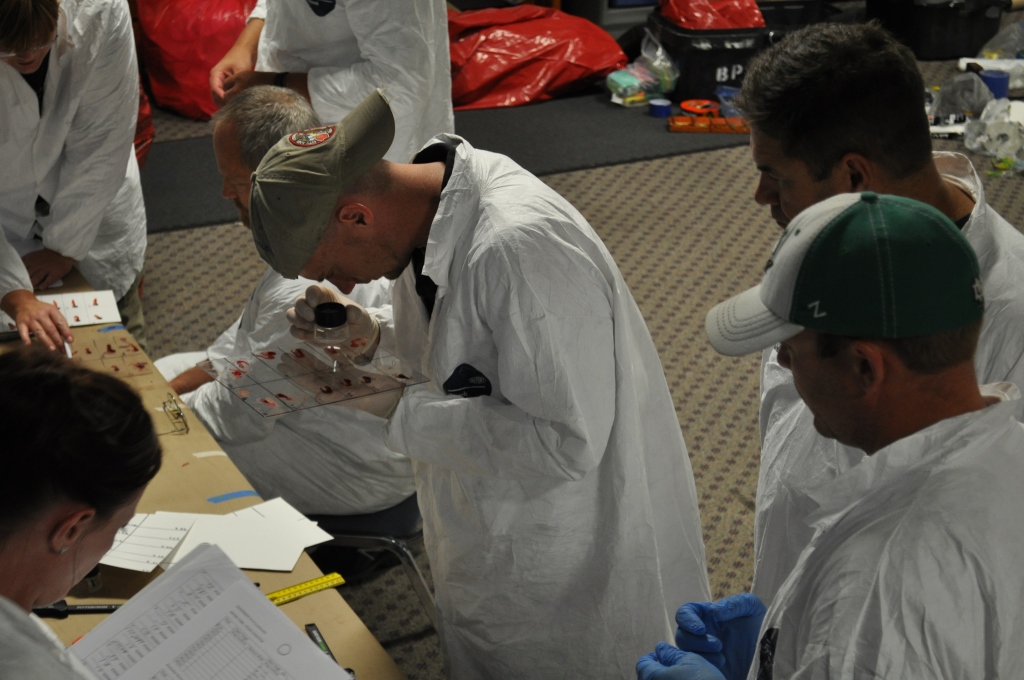

Maine State Police Crime Laboratory Hosts Level 2 Blood Pattern Analysis Course

The Maine State Police Crime Laboratory in Augusta hosted a Level 2 Blood Pattern Analysis course the last week in October. Attendees came from Maine, Connecticut and California. As part of the course, practical exercises included calculating two areas of origin for impact patterns on one target, microscopic examination of fibers as part of experimental design, examining bloodstained clothing to evaluate if a reported scenario was consistent or inconsistent with the patterns, practicing documentation of bloodstains and bloodstain patterns, and designing a scenario and then producing bloodstain patterns on clothing which other teams then evaluated. BGA blood pattern expert and course instructor Tom "Grif" Griffin noted that, in addition to an excellent course and group of participants, "the fall colors in the trees were superb and as good as photographs on any postcard!" Thank you to the Maine State Police Crime Laboratory for hosting the course in a beautiful location.

Bevel Gardner Presents at RMD IAI Training Conference

BGA Presnets at Rocky Mountain Division of the International Association for Identification (RMD IAI) Annual Training Conference

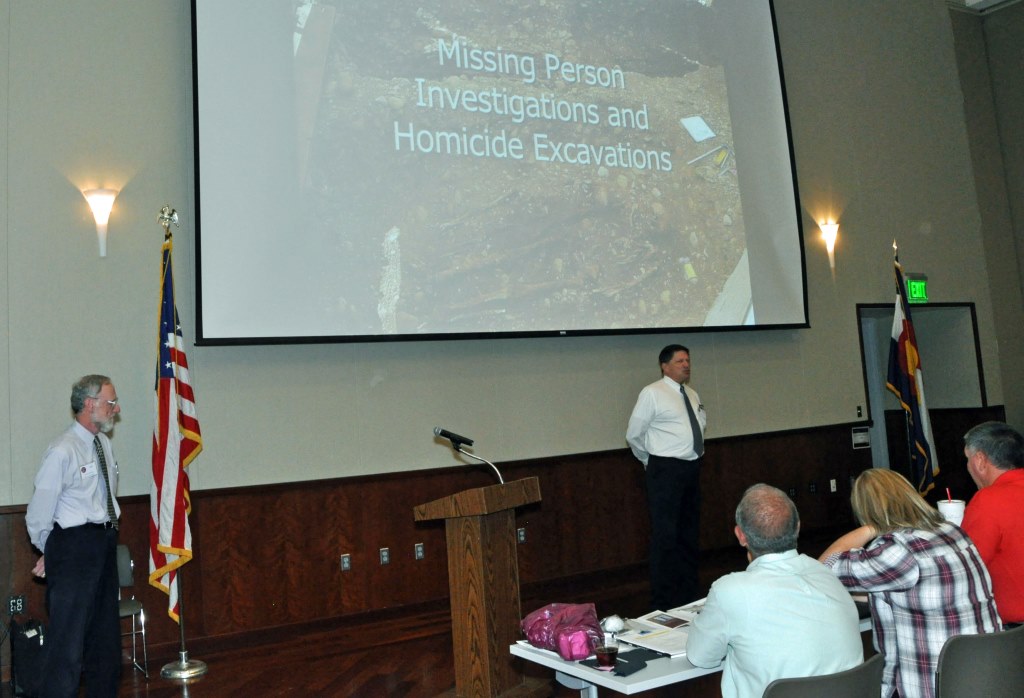

The Rocky Mountain Division of the International Association for Identification (RMD IAI) held its annual training conference October 7-9 in Grand Junction, Colorado. Conference attendees were divided into two groups and the programs were repeated on Wednesday and Thursday.

Jon Priest and Grif Griffin conducted a two-hour session on "Uncovering Missing Persons and Identification of Clandestine Graves." Topics offered by other presenters included forensic pathology, recording known tire impressions, insect collection at death scenes, postmortem fingerprints, use of metal detectors, and taphonomic research.

Jon wasthe keynote speaker at the Thursday evening dinner and installation of officers. Grif, as a past president of RMD IAI, administered the oath of office to the incoming officers and board. (Photographs courtesy of Dawn Cavins, RMD IAI Editor.)

Bloodstain Pattern Documentation Course

Bloodstain Pattern Documentation Course

Ross was at Sirchie Fingerprint Laboratories this week conducting the four-day Bloodstain Pattern Documentation course. This course was developed by BGA several years ago and is both facility and equipment intensive. Sirchie graciously helped create the necessary facilities and provides the cameras and supplies to conduct this course effectively.

The course is intended for any crime scene investigator and concentrates on proper documentation of bloodstains using the technique now known as Road-Mapping, a concept originally developed by Toby Wolson. Students learn basic pattern recognition, document two different scenes over the four days and practice skills such as proper use of presumptive tests and blood enhancement techniques. As an integral part of learning enhancement techniques, students spend a half-day practicing luminol photography techniques.

The course if offered twice a year at the Sirchie facility in Wake Forest North Carolina. Prospective students can watch for course dates at either the Sirchie web site or on the BGA calendar.

BGA at The International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts

BGA at The International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts

The International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts (IABPA), formed in 1983, is holding its annual training conference in Fort Worth this week. Kim Duddy, Iris Dalley, Ken Martin, and Grif Griffin are among the approximately 145 attendees. Tuesday featured presentations on injuries and resulting bloodstains; documentation and road mapping of bloodstains and patterns; ISO accreditation for bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA); ongoing research in tracking eye movement while examining bloodstains; high-speed photography for showing the interaction of blood being deposited on fabric; photographic perspective; and report writing. The evening ended with informal case presentations.

Wednesday featured presentations on a backspatter study utilizing human cadavers followed by BPA on fabric issues. The IABPA business meeting, conducted by President Pat Laturnus finished the morning. The 2016 conference will be held in Salt Lake City with the exact dates to be determined. Participants had their choice of attending one of three workshops during the afternoon. Ken, Kim and Grif were at BPA on Fabrics while Iris was at arterial pattern production.

BGA members have a long history of involvement in IABPA with Tom Bevel, Ross Gardner, Iris, Grif and Kim having served on various committees and/or held offices since each joined the association. Tom is a charter member and served as the first president, and Grif and Iris are also past presidents. In addition, Tom and Grif have both been honored with distinguished member status.

Induction, Deduction and BPA

Induction, Deduction and BPA

Ross M. Gardner

I always harp on the issue of criteria based analysis. I’m sure some people probably get tired of that, but it is critical and I’d like to broach the subject in a slightly different fashion in this blog, that being the manner in which we form the arguments that lead us to our conclusions.

Any conclusion offered in science is effectively the result of a logical argument. Within this argument there is some foundation (a series of premises) that lead the analyst to whatever conclusion they claim. The way in which these arguments are proposed is important. The two standard ways of looking at arguments is that of deduction and induction. Deductive arguments are those in which the conclusion MUST follow, assuming the premises are correct. Inductive arguments are those in which the conclusion Should follow, assuming the premises are correct and our sampling (the specific nature of the premises we include) is sufficient.

With these differences in mind, lets imagine for a moment that we have a thing in a hypothetical world (an object, not a mechanism) that we call a “whatchamacallit”.

A whatchamacallit is defined as an object that has specific physical characteristics, certain “taxon”, which include:

Taxon X

Taxon Y

Taxon Z

As a friend and I walk down a road one day, we come upon an unknown object lying there. As it is unknown to us, we begin to evaluate it against objects that are known. As we look at it, we see it has certain characteristics, which include:

Taxon X

Taxon Y

Taxon Z

We also see there are no other evident physical characteristics. Based on this information, I propose the following argument to my companion:

Premises:

A whatchamacallit is an object with the Taxon X, Y and Z

The unknown object I see has Taxon X, Y and Z

No other taxon are present on the unknown object.

Conclusion: The unknown object is a whatchamacallit

I have just offered a deductive argument. If my premises are correct, my conclusion must be true. The information in my conclusion in no way exceeds the knowledge presented in the premises. My friend seeing the same thing thus agrees and accepts my conclusion.

Lets also assume in this hypothetical world that we have another object, called a “thingamagig”. It is defined as an object with specific taxon as well, but for the thingamagig the taxon include:

Taxon W

Taxon Y

Taxon Z

As my friend and I continue down the road in our hypothetical walk, we encounter another unknown object. As we examine this object, we see that its characteristics include:

Taxon Y

Taxon Z

There is however more to this object, but for whatever reason, the remaining characteristic of the object is difficult to understand. Based on this information I offer my companion another argument:

Premises:

A whatchamacallit is an object with the Taxon X, Y and Z

This new unknown object has the Taxon Y and Z

My evaluation of the ambiguous characteristic suggests to me that it is Taxon X

Conclusion: The new unknown object is a whatchamacallit

I have just created an inductive argument. If the premises are true, my conclusion may well be true, but it doesn't have to be. My conclusion exceeds the information contained within the premises. I’m not really sure about the X factor and in fact I am surmising its presence. My conclusion therefore is inductive and I must accept there are other possible explanations. My more objective companion quickly points this fact out to me, offering a counter argument:

Premises:

A whatchamacallit is an object with the Taxon X, Y and Z

A thingamagig is an object with the Taxon W, Y and Z.

This new unknown object has the Taxon Y and Z

The ambiguous characteristics of the unknown object could be either Taxon W orX

Conclusion: The new unknown object could be either a whatchamacallit or a thingamagig.

My friend has returned the argument of the nature of the object to a deductive one; less precise, but deductive nonetheless. One in which, assuming I can be objective, I should readily agree with.

So how does this little hypothetical relate to our understanding of bloodstain pattern analysis? Bloodstain pattern classification should be no different. If we accept that bloodstains (no matter what we choose to call a particular stain - spurt, projected, arterial, or whatever) have certain characteristics and we evaluate unknown stains against said characteristics; all classification decisions by the BPA analyst can be defined as deductive arguments. Either the characteristic is present or it is not. There is no need to add ambiguity to this step of the analysis by guessing about or surmising a characteristic with inductive reasoning. The less specific conclusion, but as it turns out the more objective one, is the better one! Any analyst, who accepts the criteria as correct, should agree with the resulting classification.

The ultimate conclusion offered by the analyst of how that particular stain came to be in that particular scene will certainly be arrived at through induction. We accept that bloodstain patterns are a form of class characteristic evidence and we know we have to consider the stain in the unique context it was found; thus in the inductive phase of the analysis two analysts may well interpret that context in slightly different ways. This may well lead them to different conclusions about a given stain’s source within a scene. We should never be foolish enough to believe we can completely eliminate opposing conclusions. But by making all classification decisions deductive arguments, the analyst eliminates bias, keeps all viable possibilities open and in doing so becomes more objective in their ultimate conclusions.

If this idea were demanded of all analysts, that alone would eliminate the classic “This stain could be anything” claim and more importantly prevent the often times dichotomous sounding claims of opposing analysts so often heard in court. Instead of the jury hearing“It must be A” from one analyst and “It must be B” from another; wouldn’t it be better if they heard, “It could be either A or B” from both, followed by further explanation as to why either analyst felt one was more likely than the other? Imagine that, more consensus from scientists! Wouldn't that be nice?

Dealing With Ambiguous Bloodstain Patterns

Dealing With Ambiguous Bloodstain Patterns

Ross M. Gardner

Classification of bloodstain patterns based on recognition of specific criteria is a critical component of the bloodstain pattern analyst’s efforts, but it is just one part of a process that may allow the analyst to offer a conclusion as to the source of an unknown pattern found at the scene. Proper protocol demands we evaluate the stain and decide what kind of pattern it is, its classification, then we must consider the stain within the unique scene context.

There is no question that the more certain the classification of a scene pattern, the more certain any subsequent conclusion offered by the analyst will be. If the analyst has confidence the pattern was created by a streaming ejection that significantly limits the potential source mechanisms that may be present in the scene. But what if the analyst is not confident of the specific classification? Does that prevent them from offering a specific conclusion?

The answer is no, not always. Which brings us to the ever-present ambiguous pattern! Not all bloodstain patterns found in a given scene will demonstrate sufficient physical characteristics (taxon) that allow the analyst to isolate the pattern to an absolute classification. Substrate issues in particular and other variables often prevent the taxon from appearing. In those instances only a general or ambiguous pattern classification may be possible.

As an example, lets imagine encountering a series of spatter oriented in a line on a vertical surface (a doorway facing) where all of the stains are very elliptical, all are oriented with their long axes parallel to the ground and where there is no volume indicator present (e.g. no flows emanating from individual spatter). There are analysts out there who will and have testified that such a pattern “could be anything”, but that is not technically correct. The pattern is some form of linear spatter.

The mere fact that we have spatter eliminates all of the non-spatter mechanisms in and of itself. The presence of the linear characteristic eliminates any radiating or random form of spatter (e.g., impact, expiration, mist, drip) leaving us with only three potential source events. As the pattern is made up of linear spatter, the source event must be either: a form of drip trail, a form of cast-off, or a spurt. There are no other options.

Based solely on this classification of “linear spatter”, no further conclusion is possible. The stain itself is ambiguous and to force a more refined “classification” based on the limited taxon present would be subjective. But that is not the end of the story for the analyst. Context is a factor in offering any ultimate conclusion. Under what circumstances did we find the pattern and what, if anything, does that tell us?

How about considering a potential claim of drip trail? In our hypothetical, the spatter are oriented in a line, but their respective long axes are parallel to the ground. This demands the stains impacted while moving across the door face. Drips are a function of gravitational force acting on the blood mass, if associated with drips the long axes of the pattern would be oriented up and down in some fashion. The lack of this aspect effectively eliminates drip trail. That knowledge alone isn’t bad, we have now eliminated all potential source mechanisms except two: cast-off and spurt.

Lets further refine our context. Lets imagine the pattern is found on the outside facing of a doorway that opens inward. The door is standing open. The stains start on the door face near the hinges and move across the doorway towards the knob. Based on other stains, it appears the door was open when the bloodletting occurred.

Under this context, lets evaluate cast-off as a potential source event. If the pattern were caused by cast-off the directional aspect and location of the stains tells us the object was swung from outside the room, the stains impacting across the door at knob height. The individual stains in the pattern are all highly elliptical; cast-off rarely begin with highly elliptical stains (the patterns typically go from less elliptical to more elliptical), under this circumstance we can make a relatively valid prediction: If the pattern is cast-off, the there will be additional linear stains on the adjoining wall next to the doorway hinges. Before the spatter could be deposited on the door facing, droplets would have ejected from the object and struck this adjoining wall and that pattern should lead directly to the door pattern.

In our hypothetical scene no such staining is present. Does that absolutely refute cast-off? Not really. Potential explanations for this lack of stains are limited, but one possible explanation would be that something else was present blocking this adjoining wall (e.g., a person) and our predicted additional cast-off were deposited onto this unknown intermediate surface.

How about considering spurt in this context. If a spurt, the stains were directed from a position outside the door and ejected effectively in the same plane as the open door face. Under these circumstances, some valid predictions include: spatter stains may be present on the immediate adjoining wall, with their long axis oriented up and down, stains that were slightly offset and did not reach the door. If present these spatter may well demonstrate volume indicators. Additionally beyond the door, inside the room on the floor we could also expect to see spatter that struck the floor in line with the pattern on the door. Such stains might well have an evident directional component or they could be generally circular. These being spatter that were offset the other way and missed the door face completely and then simply continued on to the terminal aspect of their parabolic flight path, with the stains falling downward at the end of the arc.

In our hypothetical scene stains are found on the adjoining wall, at and below the height of the pattern on the door facing with the long axes oriented up and down. In one of the several stains present, there is an indication of volume. Circular stains are also present on the floor beyond the door. They are oriented in a line that is parallel to the pattern on the door.

Given such a context, the analyst should be quite comfortable in concluding the linear spatter pattern was caused by a spurt source. The lack of the additional indicators of cast-off and the presence of the additional indicators of spurt provide sufficient foundation for this conclusion.

So having begun with what was an ambiguous linear pattern and by considering context the analyst is able to isolate a more effective explanation for the pattern.

The pattern classification itself did not change; the pattern remains ambiguous, it is still just a “linear spatter” pattern. But the conclusion offered as to its source has changed dramatically by considering the context in which the pattern was found.

Unfortunately not every ambiguous pattern can be dealt with as effectively. At times an ambiguous pattern is just that, an ambiguous pattern. Analysts have to accept that and the reality that no effective conclusion may be forth-coming in such instances. The lack of specific taxon in any scene pattern and a subsequent ambiguous classification for that pattern may well prevent the analyst from offering any conclusion as to the source event. But keep in mind that classification is just one part of the analysis of a bloodstain. An ambiguous pattern may well be a hindrance, but it is not always a show-stopper. Once a classification is achieved, the analyst must look objectively at the unique context in which the pattern is found and applying all of their knowledge to determine if that context allows a better understanding of the pattern.

Upcoming Journal of Forensic Identification (JFI) Article

The September/October JFI will include an article written by Ross entitled “Applying Hill’s Criteria to Determine the Validity of Cause and Effect Associations in Crime Scene Analysis”.

The article discusses Sir Arthur Bradford Hill’s causation evaluation criteria, used in medicine, and applies them to crime scene reconstruction. These criteria provide the crime scene analyst with a more robust method of evaluating causation and help to eliminate cognitive bias and specifically contextual bias.

Abstract: Crime scene reconstruction involves evaluating casual connections between various actions that occur during a given incident. Analysts use critical thinking, logic and a variety of technique to accomplish this evaluation. And underlying concern in the process is contextual bias, which must be controlled to ensure that only valid casual connections are included in the analysis. In 1965, Sir Austin Bradford Hill introduced a series of evaluative factors to use when evaluating cause connection in medicine. This paper describes Hill’s criteria as they apply to crime scene reconstruction.

The article will appear in the upcoming Journal and can be found on page 801-811.

Bevel Gardner's IAI Wrap Up

Great meeting with Shiquan all the way from Beijing!

Bevel Gardner attended the 100th Forensic Meeting of The International Association for Identification in Sacramento, CA as a vendor and sponsor on August 3-5, 2015.

Tom and Grif participated in two live Podcasts to a large audience of forensic students and law enforcement investigators, where they explained what serviced BGA offers as well discussing the training, certification and proficiency testing provided by the experts at Bevel Garnder.

Liz provided the primary coverage at the vendor booth visiting with attendees from six countries. BGA received requests to send training proposals to China and British Columbia, Canada along with invitations to be a vendor at several state IAI conferences.

The Murray’s, Jim and Candy, put together a museum quality history display of The IAI’s activities over the last 100 years. Each year had a colorful floor to ceiling panel noting where the conference was held. One IAI Conference that I did not know about was held in Cuba, obviously prior to the political stalemate between the U.S. and Cuba.

A section was devoted to each of the disciplines that are certified by The IAI to include Bloodstain Pattern Analysts and Crime Scene Analysts.

The Crime Scene Certification Board (CSCB) has begun making changes in the Crime Scene Reconstructionist (CSR) recertification program. Those applying for recertification will receive a "case packet" consisting of reports (scene, forensic, autopsy), photographs, and diagrams for which they will do a reconstruction. The test will have 20 multiple choice questions about the case. A passing score is 75% which is in line with other scene certification tests. At the CSCB panel discussion on Wednesday during the IAI meeting, the board announced it is in the process of making changes in the practical portion of the existing certification test as well as reviewing different texts for test questions. The CSCB will be continuing to work on the CSR program between now and the mid-year IAI meeting.

The CSCB had a busy week meeting all day Saturday (August 1), Sunday, Monday afternoon, had the panel discussion Wednesday morning, and spent most of Thursday (August 6) working as well. This kept Grif busy as he is a member of the CSCB.

BGA signed up to be a vendor and sponsor for the 101 IAI Conference to be held in Cincinnati in the same month in 2016. Hope to see a lot of you there.

BGA Presents at IAI in Sacremento, CA

Bevel, Gardner & Associates is scheduled to attend and present training material at the International Association of Identification (IAI) in Sacramento, California August 2-8. Are you planning to attend again this year? We hope you are! If so, stop by our booth 326 to say hello and hear all about what the BGA team has been up to this year.

We are also presenting sessions during the conference. Reference the schedule below to find out when and where you can hear from our team of experts. We are looking forward to this great opportunity to grow in our field of expertise and hope you are, too!

IAI Conference Sessions

Management of Court Orders for Latent Print Examiners

Kenneth F. Martin, CLPE, CSCSA, CFWE, CBPE

Tuesday, August 4

8:00am – 8:55am

Room LLS-03

CSFO Update

Kenneth F. Martin, CLPE, CSCSA, CFWE, CBPE

Beth Lavach

President, E.L.S. and Associates

Monday, August 3

1:30pm – 2:25pm

Room GFF-27

Let Us Know You Like Us!

Bevel, Gardner & Associates wants to treat you to a $100 gift card and a copy the BGA-produced textbook, Bloodstain Patttern Analysis, 3rd Edition All you have to do is go to the Bevel, Gardner & Associates' Facebook page, click "LIKE" and SHARE our page to be entered to win. The drawing will take place on August 31, 2015. Don't miss out, do it today!

Using Testimonial Evidence as “Data” in Crime Scene Reconstruction

Using Testimonial Evidence as “Data” in Crime Scene Reconstruction

R.M. Gardner

A recent hearing I attended raised an issue regarding crime scene reconstruction, thus I’m going to shift gears from BPA for a moment and discuss this issue. It is near and dear to my heart and involves the use of testimonial evidence as “data” in a crime scene reconstruction.

In the hearing, I presented my CSR conclusions, which were minimal. The analysis supported both attorneys’ positions and thus was not particularly probative. After direct, opposing counsel began their cross and followed this line:

Q: Mr. Gardner did you have the trial transcripts available to you?

A: Yes.

Q: Were you aware that there was an eyewitness?

A: Yes sir.

Q: Did you incorporate that eyewitness testimony into your CSR effort?

A: No sir, I look at the testimonial evidence only after I have completed the primary CSR effort.

Q: (With great bravado and tonal inflection while looking at the Judge) So you didn’t think it was important to incorporate the eye-witness account into your analysis?

A: No sir, the whole function of CSR is to define objective information, which can then be used to decide if we can corroborate or refute the more subjective evidence, which includes the testimonial evidence.

Q: (Ignoring the answer, counsel repeats the prior question, with the obvious innuendo that I had screwed up)

So lets start by defining what crime scene reconstruction is. A CSR attempts to define objective actions by various parties that are occurring during an incident. Whenever possible it defines the order of those actions. The data used to define these actions include the physical artifacts, scene context and any forensics that may be forthcoming. These actions are always based on hard data and preferably with as little inference as is possible.

As Ludwig Benner pointed out some years ago, the product of this analysis is effective for providing an objective foundation on which to test the more subjective aspects of the investigation, including the testimonial evidence.

Testimonial evidence is and always has been a major issue in any criminal investigation. The criminal justice system and the criminal investigator are constantly trying to answer the question: What, if anything, should we believe from the various witnesses and participants? As far back as 1898, Hans Gross warned investigators that if they piled testimony upon testimony, they would be led from the truth. That concern hasn’t changed and it is not singularly an issue of people purposefully misleading us. The human brain and our sensory skills are a phenomenal machine for the observation of our environment. But as phenomenal as it is, it is also highly flawed. Our brain takes shortcuts, fills in sensory information and gets things wrong all the time. If you've never seen the National Geographic show Brain Games, I would suggest you watch it. It is enlightening from an investigator’s perspective. Regardless, every good criminal investigator learns from the start of their career that testimonial evidence is often flawed for a variety of reasons.

That it may be flawed is an obvious concern for the analyst, but there is another consideration. The product of the CSR is used to test the testimonial evidence; logically we cannot use that which we are testing, as the means of testing.

The bottom line is that testimony should not be true “data” in a CSR mindset. As we’ll discuss that doesn’t mean it isn’t important, but it cannot be the data that specific CSR actions are based upon. Consider a simple example:

Imagine a room where a victim receives a penetrating gunshot wound to the chest. The victim collapsed on the floor near a north wall, blood pooling around them. The victim’s left hand is bloody. On a south wall, approximately 7 feet from the victim is a swipe mark in the victim’s blood. The swipe mark is shoulder height on the wall and indicates a swiping motion left to right and slightly downward. There are no other bloodstains or evidence present that would allow one to connect the dots between the victim’s position and this swipe.

In that circumstance, the CSR analyst would likely define the action on the south wall as “Blood from the victim was deposited on the south wall, left to right, sometime subsequent to injury”.

We know it happened, but from a CSR perspective it is ambiguous in terms of how. Was it a function of the victim’s action? Was it created by the suspect’s activity? Was it a post-incident artifact created by EMS? Given the limited data, any one of these potential explanations might be valid. But lacking hard data, the analyst cannot assume one over another.

Now let’s interject an eyewitness. The eyewitness reports that the victim was present near the south wall when they were shot. The victim remained standing a moment, placed his left hand to his chest, and then placed his now bloody hand on the south wall for support. The victim then stumbled forward, collapsing to their final position.

Under those circumstances what was ambiguous (e.g., Blood was deposited) is now understood. As an analyst we have an immediate and valid explanation of how the swipe pattern came to be on the wall. The jury or analyst would look at such testimony and go “Absolutely, that makes complete sense”. But the actual situation from a data perspective has not changed. If we insert the testimony as the “data” and change the CSR conclusion to “Victim touched the wall and deposited the blood” we have introduced an act of confirmation bias. We are taking the testimony on faith and fitting the limited evidence we have to that explanation. No new hard data exists that affords the analyst the ability to say how that blood was deposited with certainty.

Without a doubt, in the context of a statement, the analyst may better understand a scene. A CSR effort often identifies that certain things are occurring, but will be unable to answer specifically how or perhaps when they occurred. In the context of testimony (admissions, confessions, eyewitnesses) placement of those actions in the CSR become clearer in the broader perspective. Using the old puzzle analogy, the pieces start to fit! But once again, the conclusions arising directly from the CSR have not changed. As the hard data has not changed, to remain objective the CSR conclusions themselves must remain ambiguous. Knowing something and believing something are two very different things. To some this is perhaps a minor nuance, but it is significant in its effect. What if the testimony is wrong, what if they are lying?

This consideration that testimony is not true data, in no way limits the analyst. Given this broader understanding based on the testimonial evidence, the analyst can still share this knowledge. One of the most effective ways is for the attorney to present the issue as a hypothetical:

Q: “Given a hypothetical situation in which a, b, c and d occurred, is your scene analysis consistent with such a circumstance?”

A: “Yes and in fact those circumstances would explain and help us understand why we saw the evidence of actions x, y, and z”.

And of course a simpler approach is:

Q: “Mr. X testified that … , did your analysis find anything inconsistent with that testimony?”

A: “No”

So believing the testimony and expressing how it assisted the analyst in understanding the scene in the broader perspective is not lost. We are simply recognizing that the cart must follow the horse – we believe the testimony, because the CSR conclusions support it and if true the testimony provides an explanation for the more ambiguous aspects of the CSR analysis itself.

There is one major exception to using testimony as data. If we are presented with a witness, who had the ability to observe and actually took note of some scene condition that was subsequently altered or is now in question, so long as the witness is generally free of agenda such information can and should be used.

I realize that some analysts believe in interjecting testimonial evidence into the analysis. I hope I have demonstrated why A) It is unwise and B) Why it is unnecessary. Whatever choices you make in your CSR efforts, always approach testimonial evidence cautiously. Never forget Gross’ admonition, as he was absolutely correct.

Students Begin Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Training in Colorado

Grif and Jon were welcomed by the Colorado Springs Police Department as they hosted a Bloodstain Pattern Analysis 1 Course. The course was a huge success with over 25 attendees from area Colorado police departments as well as Missouri, North Dakota, New Mexico, California, and Oregon.

The BPAPD program incorporates three distinct training courses of one week each. A Level I course introduces the student to bloodstain pattern analysis with significant concentration on basic pattern recognition and documentation.

Sign up for our next Bloodstain Pattern Analysis 1 course slated for November 9 - 13 in Huntersville, North Carolina

Training of International Proportions

Bevel, Gardner & Associates is scheduled to attend and present training material at the International Association of Identification (IAI) in Sacramento, California August 2-8. The IAI strives to be the main professional association for those engaged in forensic identification, investigation, and scientific examination of physical evidence. At this important annual Conference world-renowned professionals present the most current scientific educational sessions, utilizing the most efficient methodologies and technical products and advances in the identification field. The Conference offers general sessions, poster presentations, hands-on workshops, field trips, and vendor exhibits. Every forensic discipline subcommittee offers some type of training. Levels of the educational sessions range from basic to advanced.

The BGA team also participates in local IAI chapter trainings and events. Ross Gardner spent June 10 and 11 in Lake Charles, LA presenting two workshops for the LA IAI annual training conference. His training included a four-hour workshop on methodology for crime scene reconstruction and a shooting incident reconstruction (SIR) workshop. We are proud to be part of this important organization in our field - it allows us to continue to grow and develop our skills and share our expertise with others. If you plan to be at the conference, stop by our trade show booth or attend one of our workshops. We'd love to see you there!

Bevel, Gardner & Associates Training Classes are Filling Up Fast

Bevel, Gardner & Associates hosts training courses all over the country throughout the year. All of our July courses are FULL, but we do have a slate of classes and seminars scheduled for August and beyond. See a short list of upcoming classes below or visit our training page to see a comprehensive list of available training. Hurry! Classes are filling quickly.

Upcoming Classes

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis II Boulder, CO

Aug 3, 2015 – Aug 7, 2015

Shooting Incident Reconstruction Madison, WI

Aug 17, 2015 – Aug 21, 2015

Crime Scene Reconstruction II Grand Junction, CO

Aug 24, 2015 – Aug 28, 2015

Officer Involved Shooting and Critical Incident Seminar Rosenberg, TX

Sep 1, 2015 – Sep 2, 2015

Officer Involved Shooting and Critical Incident Seminar Waco, TX

Sep 9, 2015 – Sep 10, 2015

The Complex Bloodstain Pattern

If we were to distill down the most basic aspect of bloodstain pattern analysis, we could say that the BPA analyst attempts to classify an unknown scene pattern into one of the approximately seventeen pattern types (depending on the classification system this number may be slightly higher or lower). In other words we have seventeen discrete boxes (spurt, castoff, impact, smear, etc.) that we try to put the scene patterns into. This effort, when successful, allows the analyst to understand what scene mechanisms may have led to the creation of the unknown pattern and thus allow the analyst to offer probative conclusions to the court.

As much as this is the ultimate goal, it simply is not possible in every situation. As discussed in prior blogs, the pattern itself may be ambiguous showing only limited characteristics. Another reason that often distracts from this effort is the “complex” pattern.

Complex patterns come in two forms, conglomerate patterns and those created by highly dynamic events.

Conglomerate patterns are those in which a series of different bloodstain events deposit patterns onto the same surface. When this occurs, depending upon the number, the area involved and the type of patterns deposited, it may be impossible to isolate within the conglomerate the individual patterns that are present. They appear as a single pattern that doesn’t fit into any standard classification.

More problematic to the analyst is the complex pattern created by a some dynamic event. These dynamic events are far more common than one might imagine. Some typically encountered dynamic events include drip trails in which the item dripping is simultaneously swung. The resulting pattern may begin as a typical drip trail then suddenly transition into something resembling castoff and just as suddenly transition back to what appears as a drip trail. Another common form is the pattern created by pressurized streaming ejections. If the orientation of the ejection to the surface is changing within a limited area the resulting pattern may demonstrate both spurt and gush characteristics that overlap and manifests itself as a single pattern. A third common form of complex pattern occurs any time a pooling of blood deposited in the scene is impacted (e.g., a foot stomp, or hand slap), the resulting pattern may demonstrate characteristics of impact, gush and the original pooling. In these situations, the patterns created will not fit neatly into any single classification. Beyond these more common forms analysts also encounter highly complex patterns that are functionally impossible to classify or even begin to understand based solely on the pattern itself.

How does one respond to the complex pattern? First, recognize that they exist. Accept them for what they are and do not attempt to isolate them into a single classification.

When presented with conglomerate patterns, detailed study may ultimately allow the analyst to isolate the inter-mixed patterns, but there is no guarantee of this. In terms of the more common forms of dynamically produced patterns (those described above), despite their complexity the analyst will generally understand the nature of the creation mechanism. But when presented with highly dynamic events, the resulting pattern may never be fully understood. In these instances the best the analyst can do is to describe any and all characteristics in the pattern. If sufficient investigative context is present (which may include testimonial evidence) some limited explanation may be possible. Lacking such context, these patterns may remain a mystery precluding any conclusions by the analyst.

When presented with complex patterns, remember to never force a classification and stay objective when offering any conclusions. Some patterns simply cannot be explained in a given scene context.

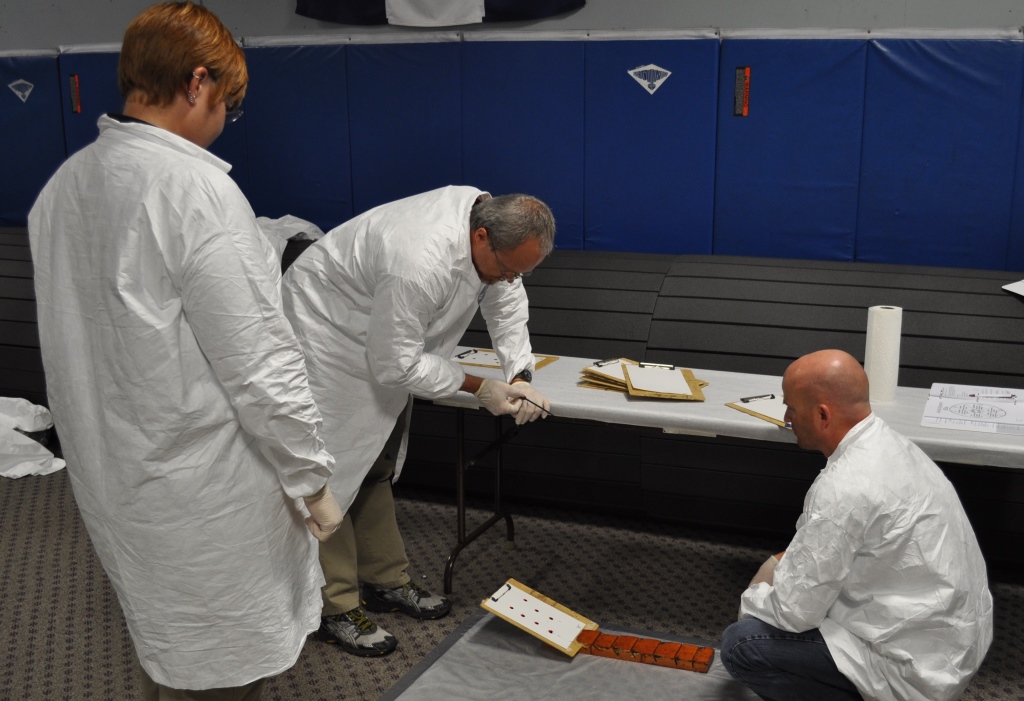

More Hands-On Experience for Students

The Bonneville County Sheriff’s Office in Idaho Falls, Idaho hosted a Bloodstain Pattern Level I course 15-19 June 2015. Ross and Grif were the instructors, with student participants from around Idaho, the Unified Salt Lake City PD and the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center.

The Level I course is a primarily hands-on course in which students create a variety of bloodstain patterns under controlled conditions, evaluating the physical characteristics of the patterns. Students also learn techniques for documenting patterns and multiple methods of evaluating area of origin of impact patterns.

LA IAI Annual Training Conference

Ross spent the 10 and 11th of June in Lake Charles, LA presenting two workshops for the LA IAI annual training conference. First up on Wednesday was a four-hour workshop on methodology for crime scene reconstruction. After a 1.5 Hr lecture, student participants were required to apply the concepts presented to evaluate an actual homicide case and decide if they could refute or corroborate a testimonial claim by a subject. On Thursday a shooting incident reconstruction (SIR) workshop was on the agenda. Once again, following a lecture, students were presented with a hypothetical police shooting and applying basic SIR concepts asked to refute or corroborate two different claims about the incident.